Among the tasks or “yogi jobs” a participant can volunteer for during silent retreats at the Insight Meditation Society, a Buddhist meditation center in rural Massachusetts, the most resonant in every sense is that of bell ringer. Before dawn and before every meditation session during the day, the bell ringers walk around the grounds and through the halls of a rambling brick building that was once a Jesuit seminary, striking a bronze bell that is held suspended by a thick strap. I remember being curled in a little cell of a room, hearing the bell sound deep and low in the distance. As the “awakener” progressed on his or her appointed rounds, layer upon layer of reverberations built up so that the ringer literally struck a chord that touched the heart—at least this heart.

I remember walking to the meditation hall with others as the bell sounded, feeling as if I were being led out of a wilderness on to an ancient path. It was as if the bell was a torch that had been passed from the distant past to lead me out of the isolation of my ordinary thought toward a greater awareness. The contemporary Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hahn speaks of waking the bell so that it can call us to our true home. We wake each other, I found that on retreat. But the home I felt called to was not a fixed abode —even a “divine abode,” which is the common English translation for the finer emotional states of friendliness, compassion, joy, and equanimity. I came to feel as if I were remembering another way of abiding with life, inwardly as well as outwardly. My true home turned out to be the fluid state of seeking and following the path to awakening.

“I had been my whole life a bell, and never knew it until I was lifted and struck,” writes Annie Dillard in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. According to discourses found in both the Theravada school’s Pali canon, and some of the Agamas in the Chinese Buddhist canon, the Noble Eightfold Path, the way to awakening and liberation was not invented but was rediscovered by Gautama Buddha. “In the same way I saw an ancient path, an ancient road, traveled by the Rightly Self-awakened Ones of former times,” taught the Buddha. I think people from different times and cultures approach spiritual practice in different ways. At least I was influenced by the American ideal of the rugged individualist. Since the Insight Meditation Society is in rural Massachusetts, I often prepared for its rigors by thinking of Henry David Thoreau, who lived alone for several years in a tiny cabin at the edge of Walden Pond. “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life.” I went on retreat because I desperately wanted to know what it means to be alive. But I went believing that one should be self-sufficient and wary of following anyone else’s path.

I was mindful that when Thoreau wrote about leaving Walden, he mused about how quickly a path can be worn in the earth and in the mind: “How worn and dusty, then, must be the highways of the world, how deep the ruts of tradition and conformity!” Somehow I missed the forest of Thoreau’s message for the romance of living in a little cabin among the trees. For Thoreau follows that burst of American individualism by concluding that when a person moves in the direction of living a more real and essential life, “new, universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish themselves around and within him…. In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty, nor weakness weakness.” It took a long time for me to register that at Walden, Thoreau found a way to abide peacefully with life—a way to live in which he was not independent and alone, but part of a greater wholeness. Through voluntary simplicity, he found a path to a greater way of living, a path to truth.

As moved as I was, I didn’t volunteer to be a bell ringer, signing up only for group jobs like pot washer or floor cleaner, seeking to be a worker among workers, another pair of hands. Although I knew that ringing the bell was really a group activity also. A friend who volunteered told me he wasn’t just waking others, but himself and also the bell. We wake each other. We offer the path the living material of our own lives. We bring the path to life.

Yet I saw how quickly a moment of open awareness would attach to memories, images, and thoughts—how quickly it would be enlisted in the cause of being a particular special “someone.” Best not to inflame this tendency even further by taking on an auspicious spiritual role, I thought. In college, I read a novel based on Dante’s Inferno, about a young African-American man making his way through various hellish American cities. One image stayed with me, the young man at the end of a bar, hiding a secret purity under a ratty old coat and a cool look. For a long time, I treated being on retreat as if I were in a rough bar. I acted as if I thought it best to keep my deepest wish and my full human nature under wraps. To risk following the one was to risk exposing the other.

I misunderstood what the Buddha meant when he told his monks to abide “independent, not clinging to anything in the world.” This was not without basis. One becomes so sensitive during a silent retreat that a harsh or indifferent glance can slice right through you, just like the bell. But slowly I learned the truth of what Thich Nhat Hahn says: “But just as the suffering is present in every cell of our body, so are the seeds of awakened understanding handed down to us from our ancestors.” I began to understand that the true independence isn’t individuality, which is clinging to self (if only for protection), but falling more deeply into life and into my true humanity.

For a long time, I thought I had to go it alone. But one day I took my seat in the meditation hall and looking around at the others, amazed and touched that so many of us managed to come so far to be together— and not just from New York or California or even South Africa but through all kinds of difficulties and challenges. And all of this common effort made to be quiet together and try for a greater awareness, unattached to particular memories or thoughts or feelings, free from being a particular someone. Wrapped in shawls or yoga blankets, sitting still with backs straight on cushions, we looked like the earliest humans, at least as I thought of them. We were also like early humans in the sense of being like children again, who seem to open to reality with their whole beings.

At first, turning the attention to essential facts of life in such conditions, to the body and the breathing, felt huge and daunting, like descending into a vast cave full of unexplored forces with just a dim flickering light. Yet, I had the sense that if I just kept going, I might come upon wonders. And over time wonders were revealed, chief among them the light of conscious awareness or mindfulness itself. Although it often seemed as if it wasn’t much brighter than a night light, I came to realize that it was the strongest force in me because unlike other parts and attachments that changed, this light seemed to be independent of outside circumstances, clinging to nothing in this world. It was amazing to discover that this little light of mindfulness—and my intermittent search for greater awareness and true liberation— turned out to be my truest home, what was most abiding.

According to the great Zen master Dogen, the path to awakening and liberation is not a line but a circle. When we sit down to remember the light of mindfulness, when we sit down to meditate or otherwise seek to awaken to what is truly abiding, we are joined by the Buddha and awakened ones from ancient times. I felt enormously supported on retreat, and I began to wonder if the Buddha’s rediscovery of the path might not have been an extraordinary act of remembering that came to benefit beings in all times.

Smirti in Sanskrit, sati in Pali, and Drengpa in Tibetan. All these words mean to remember, and they point towards a quality of understanding and living that draws on our whole being. To “re-member” or “re-collect” means to have the head and heart and body all in alignment, all collected, concentrated, and calmed. I realized that Thoreau must have discovered this state, which the Buddhists call samadhi, when he described in his journals being in accord with nature, his mind like a lake untouched by a breath of wind, his life in “obedience to the laws of his being” In a state of samadhi, the Buddha rediscovered the path to full awakening and liberation.

The Eightfold Path of the Buddha contains eight steps or trainings: right view or understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness—culminating in a higher understanding and intention. The contemporary scholar monk Bhikkhu Bodhi writes that what is commonly translated as “steps” is better described as components or strands, “comparable to the intertwining strands of a single cable that require the contributions of all for maximum strength.” Many Buddhist teachers substitute the translation “right” with “whole” or, sometimes, “recollected.” When we are in a state of inner alignment, when we are mindful, it is natural to live in a way that is more sensitive and resonant with the life around us, where non-grasping and non-harming is not a kind poverty or weakness but nobility.

In outside life there is no bell, no sitting with allies in a big hall, no stillness in which to come upon a calm lake or explore a cave. There are storms. It can seem frustratingly circular, that the first step on the path is right understanding. It seems that all on our own, we are to come to an understanding that consists of two main strands—that all our actions have consequences and that there is no inherently fixed self.

Yet there are openings. In the wake of a hurricane, for example, we lost power for four days. I collected sticks in the yard to burn as kindling in the wood stove, and hauled buckets of water into the house to flush the toilet and wash the dishes. I performed these actions in a slow and unpracticed way. My true vulnerability, my true lack of connection inside and outside, was suddenly painfully exposed. I saw, again, that I am a collection of parts, of thoughts and dreams, and that I am at the mercy of forces outside my control.

And yet I saw that this very act of seeing, of surrendering to what is and really seeing the state of affairs, brought a new understanding. A quality of mindfulness appeared that was quicker and more sensitive than my usual thought. You might say I pulled myself together. I became aware that a house grows dark and cold at night without someone to build a fire and tend it, and that it’s good to wake up to a cup of coffee and a tidy house. I became the hearth keeper, the matriarch. I saw that while I was clearly no one special at these chores, I was engaged in something useful.

It takes a long time to cook over a fire—hours! Yet this was not an inconvenience but the center of the evening. The light and warmth from the fire, the promise of warm food, the common talk of how it was coming along, and the stories as we ate—as all of this unfolded, I realized there is always another possible way of living, a way of relating mindfully to what is elemental and crucial. I also saw that you can give yourself to a task in a way that makes it an act of generosity, and at the same time a means of inner search for connection. Tending the stove, I realized that what Buddha taught may actually be possible to realize, because we and our ancestors are not separate. They live on in us in the rhythm of our breathing, in the light of mindfulness, in our capacity to open to what is. They accompany us when we seek to remember.♦

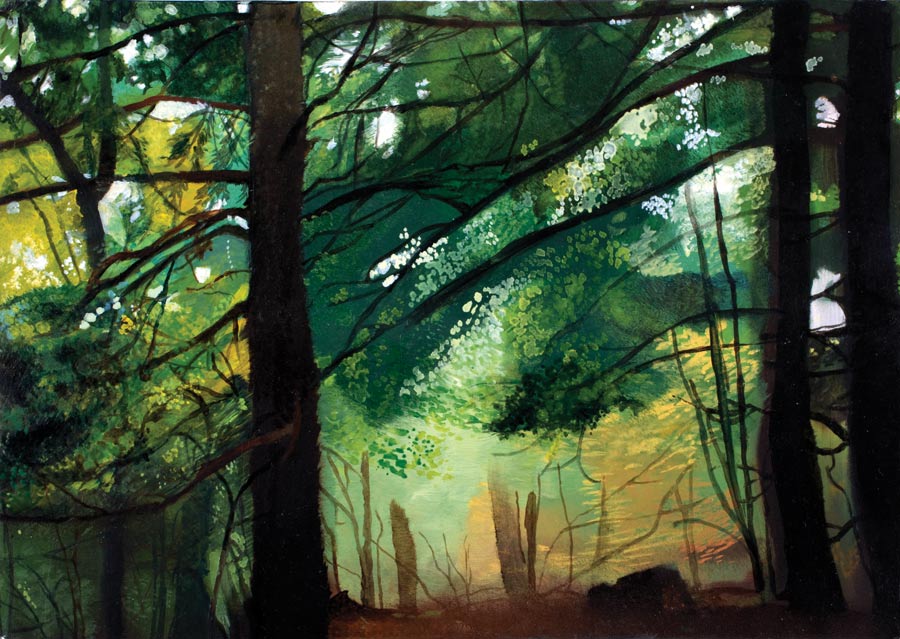

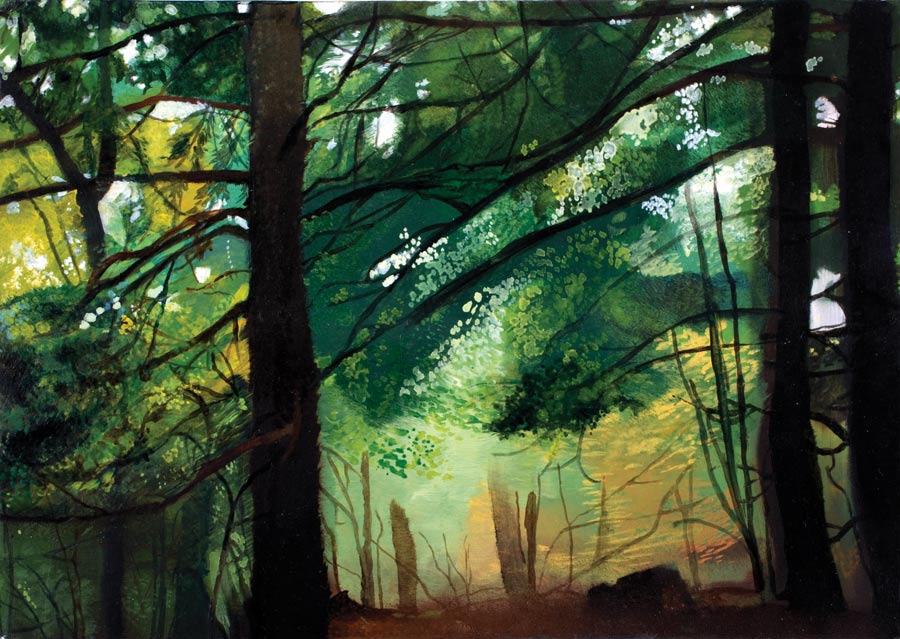

From Parabola, Volume 36, Number 4: “Many Paths One Truth,” Winter 2011-2012. Paintings by Emma Tapley. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.